Diabetes is a complex and challenging illness. When someone is managing diabetes, they want to see the entire picture—including the most accurate information possible. Though hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c or “A1C”) is the metric most often used in healthcare offices, it can be inaccurate for certain groups and medical conditions.

When an A1C isn’t accurate, it can lead to inaccurate diagnoses, mismanagement of glucose levels, and adverse health outcomes. The following populations can experience inaccurate A1C test results:

People of color

A1C can be inaccurate in people of color, especially those of African descent. Studies show that A1C values are less accurate for people of African, Mediterranean, or Southeast Asian descent.

Specifically, A1C has been shown to frequently overestimate glycemia in African American individuals. Standardized A1C values for prediabetes and diabetes are based on the DCCT trial that primarily enrolled white people and did not account for racial and ethnic variations in A1C. There are genetic differences in hemoglobin in these racial/ethnic populations, namely hemoglobin S, C, D, and E. These variants can also cause hemoglobinopathies, a group of blood disorders and diseases that affect red blood cells—which can affect A1C results, as the A1C test does not account for these differences in hemoglobin.

As a result, A1C standards may be inaccurate for some, which can lead to misdiagnosis and overtreatment, putting them at a higher risk for mistakes in treatment.

Older Individuals

As people age, we are more susceptible to red-blood cell turnover rate changes. Older populations have a higher risk of conditions that affect these rate changes and as A1C is dependent on the length of time the red blood cells circulate in the blood, this can affect A1C results and make them inaccurate—either higher or lower than the actual average blood glucose.

A1C also does not show hypoglycemic episodes, as many studies have reported that hypoglycemia is not limited to people with a low A1C. Hypoglycemia is a risk factor for frailty in older populations, which is directly associated with higher mortality in older adults.

Solely using A1C in diabetes management could increase hypoglycemia risk in older people with diabetes—meaning more hospital visits and potentially dangerous situations. For older adults, CGM should be used for glycemic goal setting, as CGM metrics like time in range can provide accurate insights into hyper-and hypoglycemia.

People with kidney disease

Research shows that A1C may be less accurate for people with chronic kidney disease (CKD), especially those with advanced CKD.

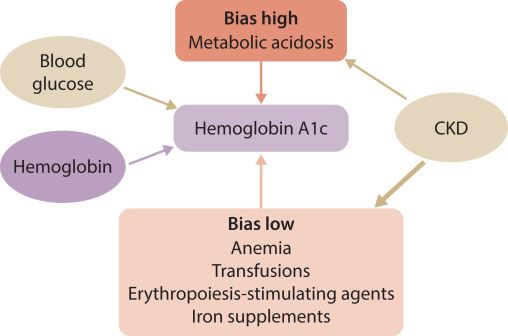

Common CKD comorbidities and treatments, including anemia, blood transfusions, iron supplements, and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, can result in a lower A1C, while metabolic acidosis can result in a higher A1C. These inaccuracies can have major implications on daily diabetes management, possibly resulting in increased frequency of hypo-and-hyperglycemia.

Image: Effects of chronic kidney disease (CKD)–related factors on glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c).

As A1C is measured by the red blood cell life span, when the kidneys begin to fail, they are unable to remove acids that build up in the body. This buildup of acids (metabolic acidosis) speeds up the process of glucose binding to hemoglobin, causing A1C to appear to be higher—as the red blood cells’ life span becomes shorter.

Conversely, comorbidities like anemia and treatments like blood transfusions and CKD medications can reduce red blood cell production, meaning there’s less hemoglobin for glucose binding, resulting in a lower A1C.

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) global guidelines encourage CGM use in people with CKD. Recent evidence has shown that increasing time in range can lower risk of kidney damage in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Time in range and CGM can give an accurate picture of a person’s management with CKD—and it can be a more accurate indicator of the risk of complications across the board, as well as a powerful tool for self-management.

Pregnant Individuals

There is conflicting evidence on whether pregnancy overestimates or underestimates A1C—but we know that pregnancy is a factor in creating inconsistent and inaccurate A1C test results.

Similarly to aging populations, pregnancy changes the life-cycle of the red blood cell, which can affect A1C. It’s also been found that using A1C could provide false reassurance if it’s used to measure glycemia in mid- to late-gestation.

Diabetes management is extremely important for fetal development—inaccurate measurements of A1C can be serious. It’s vital to be able to not only get an accurate measure of glucose levels, but a full picture. A1C doesn’t capture swings in glucose and misses the opportunity to provide actionable insights into daily management.

Alternatives to A1C

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) provides accurate glucose levels and metrics that show the entire picture of someone’s diabetes management.

Time in range (TIR) shows the average percentage of time someone spends within their target range of 70-180 mg/dl , time below range (<70 mg/dl, TBR), and time above range (>180 mg/dl, TAR) and it provides this information daily, weekly, monthly and quarterly This allows people with diabetes and their healthcare teams to see the full picture—and identifies what needs to be done to improve glycemic control.

Click here to learn more about how time in range can help people with diabetes thrive.